The Challenge of Maintaining Distributed Systems

The progressive increase in the number of interconnected devices, leads to a rise in the costs associated with maintaining distributed systems. This creates significant challenges in implementing software services on a global scale using the traditional approach of individually programming each agent. This situation drives the search for solutions aimed at improving the autonomy of computing systems and reducing their complexity.

Aggregate Programming as a Relevant Approach

In this context, Aggregate Programming1 (AP) emerges as a relevant macroprogramming approach. It is based on the functional composition of reusable collective behavior blocks, with the goal of efficiently achieving complex and resilient behaviors in dynamic networks.

Key Properties of Aggregate Programming

- Self-organization: the system as a whole is capable of achieving globally coordinated behaviors through decentralized interactions among individual devices.

- Self-coordination: devices autonomously exchange information and adapt their behavior to maintain coherence, even in the absence of centralized control;

- Self-stabilization: the system naturally converges to a desired stable state despite transient disruptions or changes in the network.

- Resilience: the system is inherently robust to node failures, dynamic topology changes, and unpredictable environmental conditions (e.g., wireless interference, sudden weather changes affecting sensor networks, or physical obstacles disrupting communication), ensuring continued functionality under adverse circumstances.

- Scalability: the system can efficiently handle a growing number of devices while maintaining low communication overhead and computational efficiency. As the network size increases, the system continues to provide predictable response times and stable resource consumption, ensuring overall performance in terms of latency, throughput, and fault tolerance.

Aggregate programming finds its conceptual roots in Field Calculus2(FC), a minimal functional programming language designed for the specification and composition of collective behaviors. FC provides a formal framework for expressing distributed algorithms in terms of computational fields, enabling concise and declarative descriptions of large-scale system behaviors.

Building on this foundation, Aggregate Programming defines basic building blocks, which serve as foundational mechanisms for collective behavior.

For example, broadcasting and gradient formation are widely applied in sensor networks to propagate information efficiently.

Event detection and consensus play a crucial role in distributed monitoring systems, enabling nodes to agree on the occurrence of specific conditions despite local disruptions.

Similarly, clustering and leader election are essential in ad-hoc mobile networks to establish hierarchical structures and coordinate actions.

These building blocks lay the groundwork for more advanced and resilient applications across dynamic and large-scale environments.

Practical Applications of Aggregate Programming

Aggregate Programming has demonstrated its versatility in solving complex coordination problems in distributed systems. Practical use cases include:

- Robot Swarms3: AP enables coordinated behavior in fleets of autonomous robot, such as formation control, coverage, and search-and-rescue operations, where dynamic and resilient coordination is required.

- Crowd Management4: AP supports applications for monitoring and controlling crowds, including density estimation, anomaly detection, and safe dispersal strategies in large-scale events or emergency scenarios.

- Environmental Monitoring: sensor networks employing AP can collectively estimate parameters like pollution levels, temperature gradients, or wildfire spread by aggregating local measurements efficiently.

- Vascular Morphogenesis5: an early application of AP was demonstrated in the context of vascular morphogenesis, where Collektive was used to model self-organizing biological patterns.

These examples highlight how Aggregate Programming simplifies the design and implementation of robust, scalable, and adaptive behaviors in dynamic and decentralized systems.

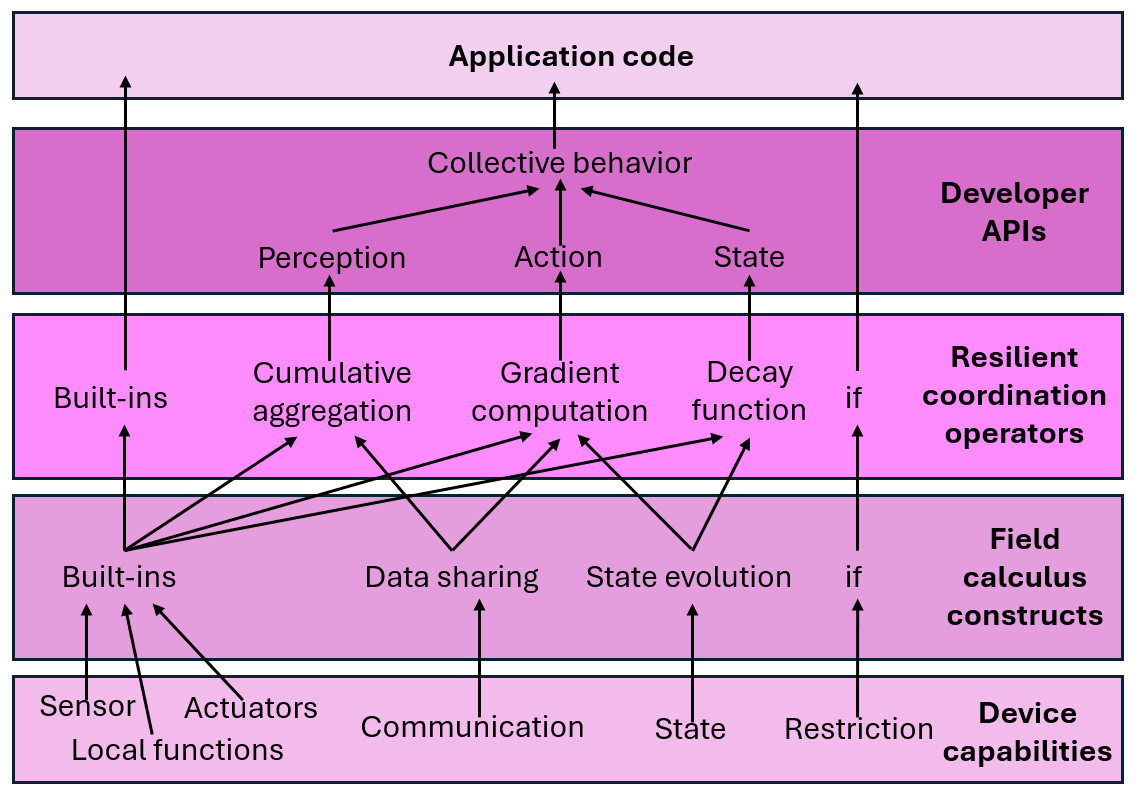

Levels of Abstraction in Aggregate Programming

Through multiple levels of abstraction, aggregate programming mitigates the complexity involved in distributed coordination within IoT network environments:

Field Calculus Constructs

This layer represents the interface where aggregate programming interacts with the external environment. It is composed of device infrastructure and non-aggregated software services, which together form the system's lowest layer. As depicted in the figure, this is the second layer from the bottom.

A key abstraction provided by Field Calculus is the notion of a field, inspired by physical phenomena.

In this abstraction, each networked device contributes a local value, forming a distributed structure over the system.

For example, temperature sensors might define a field of ambient temperature values, while smartphones might contribute fields of movement directions or displayed notifications.

Field manipulation and creation rely on fundamental constructs that enable:

- Computation over distributed data: functions allow the execution of operations on data distributed across the system, including both built-in and user-defined logic. These computations can represent readings from sensors or outputs to actuators.

- State evolution over time: mechanisms are provided to model how a device's local state evolves, based on previous states and new inputs from the environment or the system.

- Interaction with neighbors: constructs enable devices to collect and aggregate information from neighboring devices, supporting spatial computations like detecting the closest node or propagating values across the network. Notably, value propagation requires a combination of state management mechanisms (for maintaining state across computation rounds) and neighbor interaction constructs (for accessing neighbors' values), enabling the definition of distributed algorithms such as gradient formation or information spreading.

- Conditional branching in the network: conditional mechanisms allow devices to behave differently based on local or global conditions, partitioning the network into distinct regions that execute different operations.

Together, these constructs enable the creation of robust and flexible behaviors that emerge from the aggregation of local device interactions and computations.

Resilient Coordination Operators

The next level of abstraction introduces a set of resilient coordination operators designed for robust distributed computations.

These operators enable the system to adapt reactively to changes in network structure or input values, ensuring self-stabilization and resilience.

Key operators include:

- Gradient formation and value propagation: operations that calculate distance fields and propagate values across the network based on these gradients. These operators are crucial for tasks like broadcasting, projection, or region-based computations, where spatial relationships between nodes are important.

- Cumulative information gathering: mechanisms for aggregating information along gradients, such as summing values or collecting information towards specific regions of interest.

- Flexible temporal decay: constructs that manage countdown processes or decay functions, enabling time-based coordination that adapts to changing rates or conditions.

These operators abstract common coordination patterns, simplifying the development of distributed applications by allowing developers to focus on high-level behavior and global objectives, rather than low-level implementation details.

Developer APIs

Libraries developed using fundamental operators can leverage and combine these operators to create a pragmatic and user-friendly API (Application Programming Interface). These libraries represent the penultimate layer in the structure illustrated in the figure, on which application code is based.

Many distributed actions and information diffusion processes can be abstracted into high-level API functions that encapsulate the complexity of the underlying coordination logic.

Example: Gradient Computation

The following example demonstrates a simple API function for computing a distance gradient. This function calculates the minimum distance from a set of source devices within a dynamic network. Gradients are a foundational construct in aggregate programming, enabling behaviors like distance estimation and value propagation.

Note: when defining new aggregate functions, it is recommended to use extension functions on the aggregate interface. This promotes reusability and consistency as follows:

fun Aggregate<Int>.gradient(distanceSensor: DistanceSensor, source: Boolean): Double =

share(POSITIVE_INFINITY) {

val dist = distances()

when {

source -> 0.0

else -> (it + dist).min(POSITIVE_INFINITY)

}

}

These APIs enable developers to implement sophisticated behaviors within dynamic networks without needing to delve into the low-level details of aggregate computations.

Footnotes

-

J. Beal, D. Pianini, and M. Viroli, “Aggregate Programming for the Internet of Things,” Computer, vol. 48, no. 9, pp. 22–30, 2015, doi: 10.1109/MC.2015.261. ↩

-

G. Audrito, J. Beal, F. Damiani, and M. Viroli, “Space-Time Universality of Field Calculus”, in Coordination Models and Languages, 2018, pp. 1–20. ↩

-

G. Aguzzi, G. Audrito, R. Casadei, F. Damiani, G. Torta, and M. Viroli, “A field-based computing approach to sensing-driven clustering in robot swarms,” Swarm Intelligence, vol. 17, no. 1–2, pp. 27–62, Sep. 2022, doi: 10.1007/s11721-022-00215-y. ↩

-

B. Anzengruber, D. Pianini, J. Nieminen, and A. Ferscha, “Predicting Social Density in Mass Events to Prevent Crowd Disasters,” Lecture notes in computer science, pp. 206–215, Jan. 2013, doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-03260-3_18. ↩

-

A. Cortecchia, D. Pianini, G. Ciatto, and R. Casadei, “An Aggregate Vascular Morphogenesis Controller for Engineered Self-Organising Spatial Structures,” in 2024 IEEE International Conference on Autonomic Computing and Self-Organizing Systems (ACSOS), 2024, pp. 133–138. doi: 10.1109/ACSOS61780.2024.00032. ↩